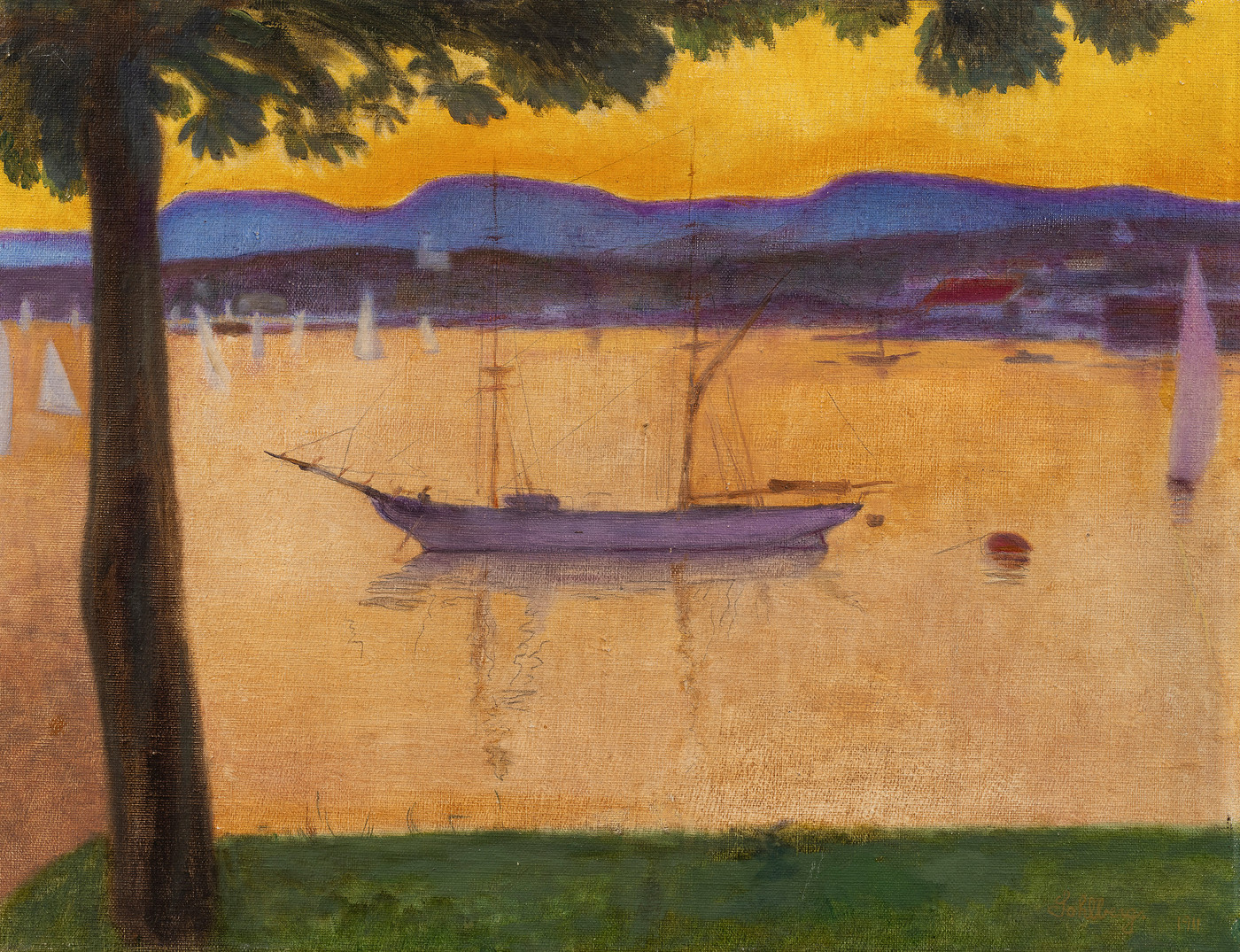

Oil on canvas, mounted on board

75x88

Signed upper left: Karsten -15

Annotated on verso: "Ludv. Karsten: "Ved vinduet" 1915.".

Estimate

NOK 400,000–600,000

Oil on canvas, mounted on board

75x88

Signed upper left: Karsten -15

Annotated on verso: "Ludv. Karsten: "Ved vinduet" 1915.".

Estimate

NOK 400,000–600,000

Ludvig Karsten's women in interiors

There is not much research on Ludvig Karsten, and if you disregard Nils Messel's master's degree and the monograph Ludvig Karsten (1995) and Pola Gauguin's Ludvig Karsten (1949), Karsten is only briefly mentioned in collective literary works and articles on Norwegian art history. Naturally, therefore, Messel's archive-based research has had a lot to say to my investigations and is the starting point for my mission to look more closely at Karsten's motifs, and especially his women in interiors.

On the other hand, I would like to claim that Karsten's treatment of the body and the interior testifies to a desire for balance, where the space and the body are connected and dependent on each other in the images´s composition. In contrast to Messel, I see how Karsten gives the objects a stronger stability in form than the body, which stands in contrast to our perception of the world where the human is the main focus, as we know from portraits.

The relationship between space and body receives a unique treatment in Karsten's art, because they take on a hybrid form, where the boundaries sometimes are unclear. This limitlessness in the composition is rooted in his formal strengths such as color and stroke, which is already an established truth in art history's narrative about Karsten. The question is whether Karsten's interior motifs are randomly chosen to explore the possibilities of colors and strokes, or whether Karsten saw them as an opportunity to explore an early abstraction of the motif.

Karsten's woman as empathetic and asexual

Commited to look more closely at Karsten's motifs, and especially his interiors, it is natural to also implement interiors with figures in such an investigation. The figure in At the window 1915 is a woman, and the motif opens the possibility of looking at it more closely through feminist art theory by Mariela Cvetic and Griselda Pollock ,in the analysis of the female figure and space, particularly based on their theories about the woman's connection to space, home and interior.

Linda Nochlin's essays in Representing Women (2019) discusses the different roles of women as the subject in art, at the end of the 19th century and into the beginning of the 20th century. In the various essays, Nochlin addresses the portrayal of women in various types of motifs. Even though Nochlin does not specifically discuss women in interiors, her theories have similarities with other forms of representations, and are of great value in an analysis of Karsten's representation of women. Nochlin's feminist art theory analyzes the female subject in the motif in the quest to uncover structures and attitudes that are symptoms of historical, political, and relational attitudes towards women. One such example is the attitude towards the woman as a sexual object for the “male gaze” in the art of the given period. Naturally enough, it is inevitable to discuss Karsten's woman in interiors, without being critical of the male painter's gaze, in this case Ludvig Karsten's gaze.

As a result of changes in society that large parts of Europe experienced in the wake of the industrial revolution, new social structures influenced what we see in the visual arts. Griselda Pollock and Mariela Cvetic discuss this in their theories about motifs from what were considered the feminine spaces of the home, such as the living room, the bathroom, and the bedroom. Pollock and Cvetic believe these were rooms in the home that belonged to the woman, but to which the man nevertheless had complete access.

Nochlin also highlights upper-middle-class familial structures and the new role of women in marriage, that was driven by social aspirations and economic security. Nochlin believes that the mother's role in this structure was characterized by morality, ambitions, and a closeness that at times appeared paradoxical, as it was more provoked by an institutional matrix than by mutual affection. The result was marriage, a domestic atmosphere and intimacy without a sexualized tone, where the woman was established as the super-ego of the asexual. Such de-sexualisation of the wife and mother legitimized the man to have a sexual affair outside the home, in the form of brothels and prostitutes. The prostituted women also often figured as models for act drawing at the academies, as well as permanent models for artists. This often explains why the analysis of female motifs by male artists was colored by a superior male gaze and a unbalanced relationship between the paying customer and the woman. This is probably why the relationship between model and artist, has of this been a much-discussed field within feminist art theory. This Central European attitude towards the domesticated asexual woman and the performing female prostitute must have been a familiar phenomenon to Karsten. Either through his stay in Paris, Copenhagen, or his travels through Europe. Whether this attitude was not to be found in Norway is difficult to say, but with Christian Krohg's tendentious novel Albertine (1886), at least the social and political challenges that arose in the wake of widespread prostitution in Kristiania were addressed. Karsten may have had an awareness of how he portrayed the woman in several of his motifs as a model, seen in the light of Krohg's social criticism.

When Gunnar Danbolt describes Karsten's Declining nude from 1909, he describes the formal qualities of the motif, where the woman's body melts into the surroundings in the absence of clear contours or lines. The body also mirrors the surroundings in the use of color, to give the subject an overall harmony and resonance. Messel analyzes the same motif in Ludvig Karsten(1995), but in a far more sensual tone than Danbolt. Messel also places the motif in the context of Karsten's brief affair with Agda Holst in Paris in the winter and spring of 1909. The sensuality and sexual undertones of the motif are highlighted as a turning point in Karsten´s motifs after painting typical tendency motifs of the period. Declining nude thus appears as a change in Karsten´s motifs, while at the same time being highlighted as one of his images that reveals an interest in artistic continuity. In this motif, Karsten has also emphasized the surroundings of the subject, and deliberately created a harmony between body and space. We also see this in At the window 1915, where the room's character and body slide seamlessly into each other. This dissolution of the body, and thus a dissolution of the carnal model, creates a distance that is experienced as non-sexualizing, but humanizing. Karsten's use of these painterly effects, corresponds to Nochlin's idea of the woman as a dynamic figure who cannot be captured in the painting in a fixed image:

"Woman .... cannot be seen as a fixed, pre-existing entity or frozen image, transformed by this or that historical circumstance, but as a complex mercurial and problematic signifier, mixed in its messages, resisting fixed interpretation or positioning despite the numerous attempts made in visual representation literally to put ´woman´ in her place.”

In At the window 1915, the woman lacks clear facial features, which reinforces the impersonal and eliminates the anchoring of the motif in reality. The woman in the motif appears as an object or a figure of the same value as the rest of the motif's structure. The room is part of her body, and her body becomes the room, through Karsten's dissolved contours and non-personifying execution. I claim that this is an incipient abstraction in Karsten's execution of the female figure. Does this mean that Karsten is indifferent to his portrayal of women, and isn't that just as condescending as the "male gaze" that Nochlin describes?

If we look more closely at how Karsten portrays the woman, we can see similarities in pose and placement with older art. With Karsten's interest in the old masters, and what Danbolt refers to as his penchant for painterly continuity, it is likely that Karsten's placement of the woman and her pose may have been active means of promoting an intellectual representation of the woman. The depiction of the contemplative and thinking woman reinforces the idea of the woman's role as a counterweight to the man's active role in the public life: the woman is an intellectual and creative being. Such a depiction of the woman as a contemplative is a well-known motif, among others depicted by James McNeil Whistler's (1834-1903) in Arrangement in Gray and Black: The Artist's Mother(1871) and by Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) in Portrait of Katherine Kelso Cassatt (1889). This representation is also empathetic, in contrast to the sexualized prostitute, and thus frees Karsten from a traditional “male gaze”.

In order to understand why Karsten has chosen to give the woman a passive role in the composition, we need to focus on who is looking, and not who is being looked at. The woman's mental absence and unapproachability can be seen as proof that she is alone in the interior in which she is placed. She does not respond to external contact, because she is alone, not aware that she is being watched. Such an interpretation confirms what I call the image´s intimacy, because there is a presence of absorption, and therefore a lack of communication between the subject in the image and the viewer. Nevertheless, the woman in the interior appears close and recognizable to us, by representing a homely atmosphere. At the same time, she is anti-theatrical in her presence in the motif, because she does not communicate directly with us, and therefore shuts us out of the same room we are invited into.

The text is an extract from the Master's thesis Intimate and Dissolved. Ludvig Karsten's exploration of body and space (2022), by Luisa Aubert